DRAFT: This line will be removed when the initial version of this is finished.

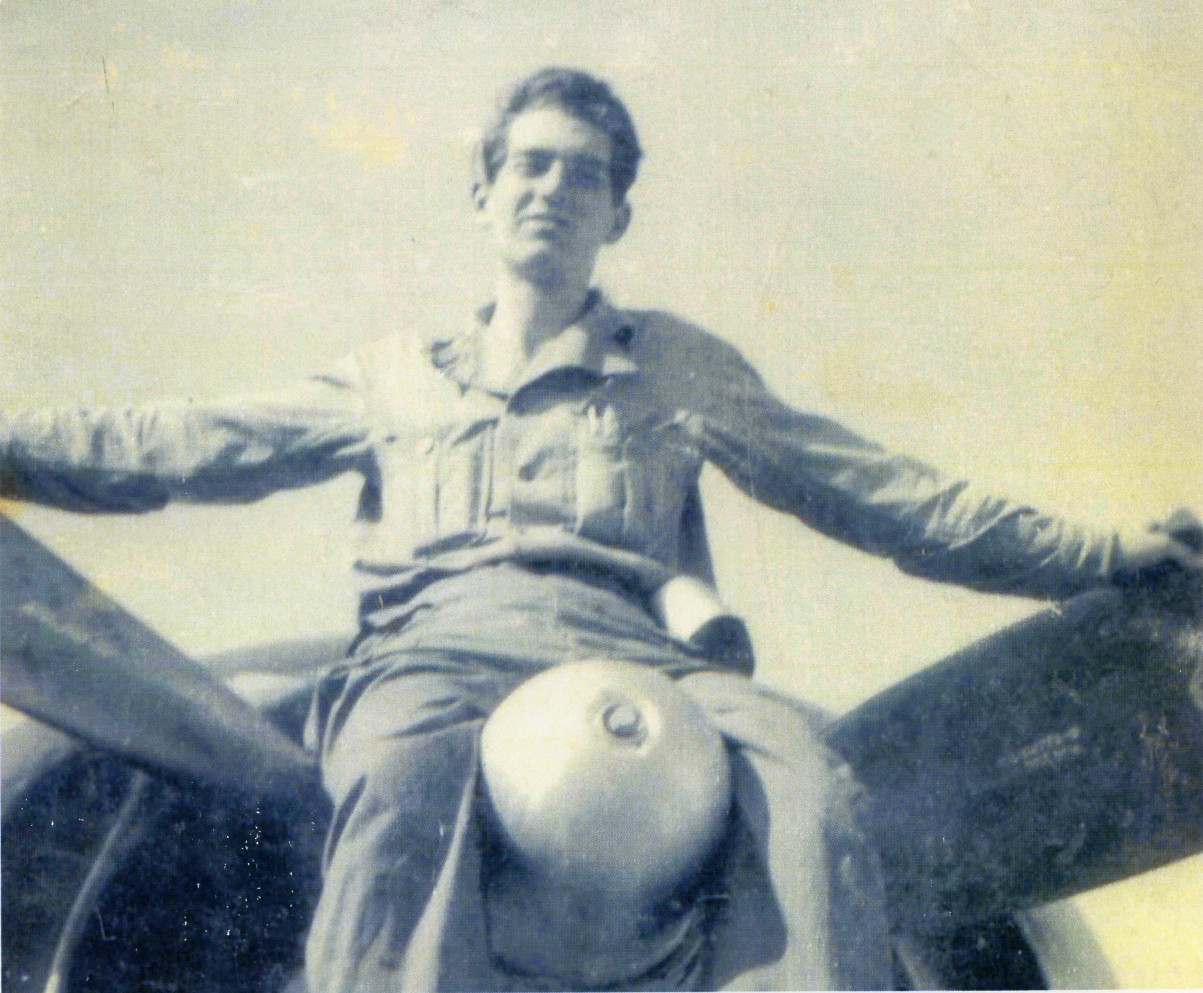

This is my dad Jim during World War II, living up to the nickname his ground crew mates gave him: Paddle Props. He taught me an immeasurable lot. I paid close attention to all that he told me until he became a devout Christian (and I tried very hard to follow his lead with that for a few years overlapping high school). And even after that, right up to when he died in my arms I kept on learning from him.

In the late 50s to early 60s we lived in Montgomery Alabama as dad helped build and operate one of the SAGE computer sites for the Air Force. We’d go down to Ft Walton Beach Florida for long weekends and sometimes my cousins Cathy and Steve and aunt Pat and uncle Jack came down from Michigan to join us. During one visit there I remember one morning dad explained to us that he’d fallen asleep while floating on his back in the gulf. When he woke up the shoreline was quite distant but he had no trouble getting back. I listened to this with interest, imagining how comfortable with one’s self somebody would be to let themselves drift out into the ocean and be confident they could get back. Actually it was silly chance he fell asleep and I suspect he wasn’t asleep for long, but long enough to have a story. But this story sums up the notion that my dad wasn’t easily frightened.

During WWII he was part of the ground crew keeping B24 bombers flying on a base in southeast England. His part was keeping the Norden bomb sights and Honeywell automatic flight control systems going, training bombardiers after equipment upgrades and, most especially, joy riding. He flew every chance he got. The other bomb ground crewmen were very happy for him to fly instead of them. I remember thinking exclusively about how convenient it was that the others didn’t want to go on flights to test or adjust the equipment and that gave dad more time doing what he loved. He’d made model airplanes from an early age and before joining the Army (there was no Air Force yet) he’d worked at the giant B24 assembly lines in Willow Run in Michigan. He told funny stories about a bombardier once flubbing his instructions and dropping practice bombs in a row of people’s back gardens (English garden == American yard). Another time he ran out of oxygen but described it as funny when time slowed down and although he was moving toward a fresh bottle on the other side of the plane just a short distance away he couldn’t manage the swap but a crewman spotted him and finished the swap. I never once considered what a big deal that brush with death constituted. Apart from the fact I would not have been had his life ended back then, the notion he wouldn’t get through that just didn’t jibe with how I imagined my dad.

Flash forward to my first motorcycle period from age 14 to 19. I road the wheels off three bikes: a Yamaha 80, Honda 150 and Bultaco Metralla. Dad borrowed them a lot, going out for a short ride and bringing it back with a big smile on his face or a funny story about embarrassing the local four wheel drivers. One day he went for a ride with me on my Honda 150. He encouraged me to give him a thrilling ride, so I went for it, approaching 10 10ths part of the time on sections of a seven mile loop road through a park on Mt Sano along side Huntsville, AL. But I forgot the little dip in the middle of a specific left hander and as it came into view there was no time to stand the bike up and reduce speed before finishing the corner. We went into the dip and for about a second’s eternity we were at the mercy of the coefficient of friction of the center stand in addition to the tire patch of the two tires. There was a flat rock face on the outside of the curve and we would have been killed instantly had I low sided the bike. It was a few years later before I screwed up the courage to explain to my dad how close we came to buying the farm on that curve. His reaction was a combination of “I know” and “No worries.”. This jibed with the attitude he taught me as he was teaching me to park a car with great precision and we’d come within an inch of hitting an adjacent car and he’d applaud my successful learning trial and respond to my momentary horror with “a miss is a mile.”

Dad excelled in what he did. He was the oldest recruit by a number of years among the other recruits to IBM for the Sage work. They nick named him The Old Man. He confided in me by his body language or a chance remark to Mom how he was occasionally unsure of himself to be able to keep up with the new university graduates. Dad hadn’t finished his EE degree at Michigan, filling in gaps while repairing TVs and radios and making one off high performance gear for his amateur radio boss. Dad busted his buns learning all that was presented by the year’s training at IBM/Kingston from about 1957-1958. I still remember him patiently sitting me down at the kitchen table and drawing the schematic of a transistor-based flip flop (“bistable multivibrator” in those days) and slowly explaining to me exactly how it worked. He never talked down to me. He treated me like a buddy who happened to be very, very short. Around that same time he helped me build a single tube radio into a coffee can.

But the Sage work was hard as a m**** f****. In their typical infinite but misguided attempt to be fair, IBM rotated the shift work. Sage was a 24/7/365 project to get the country’s air defense network upgraded ASAP. Dad could never adjust to the shift work and had terrible trouble sleeping. A side effect of that was for me to learn how to move through a house while making no sound. I still practice that today to avoid waking my wife. But the rotating shifts seemed to drive dad to use some of his off time to drink and the effect of the shift work on my mother was very severe. It wasn’t helped by the fact that at the time, from the perspective of the only yankee kid on the playground, I judged Montgomery to be the worst place on the planet and still can’t avoid negative thoughts and the odd disparaging remark about it despite the fact that many of the bigoted f***tards moved east out of the city to their safe and shiny fortress suburbs. My brother Dave and I played with the black kids that lived behind our neighborhood and mom and dad were friendly to them although we had a tremendous language barrier with our northern American and English accents and their strong dialects.

But eventually Dad and the rest of his team finished training the Air Force guys and gals to keep the Montgomery Sage site ticking like a watch and he was free to change projects. He chose the Saturn V Instrument work going on in Huntsville and on a very joyous day in January, 1963 between school terms we plowed through the snow of dad’s friends place in Decatur, spent a few nights with them and then got to a motel in Huntsville while mom and dad shopped for a house.

Huntsville was an oasis full of fascinating people and dad simply glowed with satisfaction to be out of Montgomery. He took on the engineering work to help adapt and test two pieces of gear being developed by Space Craft Incorporated (aka “SCI” that morphed into a large contract manufacturing firm). One was a transponder and the other was the command decoder. Dad would give me regular, detailed reports of what he’d done on a given day and, as usual, I soaked it up. trying hard to remember all the terms to look up when I could. He gave me access to his technical library.

But it wasn’t long before dad began to go through heavy changes. I don’t recall us going to church much in Montgomery, but in Huntsville it became a regular thing, much to mom’s chagrin.